Today we’d like to introduce you to Jo Ann Rothschild.

Jo Ann, let’s start with your story. We’d love to hear how you got started and how the journey has been so far.

As a child, I saw early 20th Century European art at the Art Institute and in my great aunt Maxine’s collection. Paintings and sculptures made sense to me in a way that the conversation of the grown-ups, did not. I imagined the artists were talking directly to me.

I went to Bennington College as a writer, but the opportunity to create art thrilled me. I switched my major to painting. In my final year in college, which I spent in absentia in Chicago, I saw a doe and 2 fauns running across a field. realized that I cared more about the rhythm of their flight than their stationary form. I made my first mature work: an etching with marks corresponding to the rhythm of the deer’s flight. This began a lifelong interest in rhythm and mark.

At the same time, I was given tickets to the rehearsals and performances of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. I would go from the studios at the art institute to orchestra hall. It was a wonderful experience. I began to think of the grid as equivalent to the staff in music: the placement and size of marks as corresponding to notes and layers of paint providing alternate tonalities and themes. These were seminal discoveries for me, and though my work may not show a grid, and marks may not always be isolated, this understanding anchors my work. After college, I moved to Boston.

I joined the Boston Visual Artists Union and the Experimental Etching Studio. Through both institutions, I met other artists and had opportunities to exhibit. Sometimes praise has been substantial: I was the first recipient of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts Maud Morgan Prize and received a grant in painting from the Massachusetts Cultural Council. I was often well reviewed and exhibited in schools and museums. But there have been times when I’ve struggled to find places to exhibit and felt as though I was working in the dark. It is crucial to continue working regardless of the public response.

In difficult times self-confidence, the shared interest of colleagues, and the fascination of the work itself makes painting possible and pleasurable. It is interesting. I am also fascinated by one thing seen beneath another, and by other artists: those who preceded me as well as my contemporaries. I work on both a large and a small scale. I make paintings as well as prints, and though primarily an abstract painter, have in the past few years examined the figure in life drawing: sometimes a leg or a hand will show up in an abstract piece.

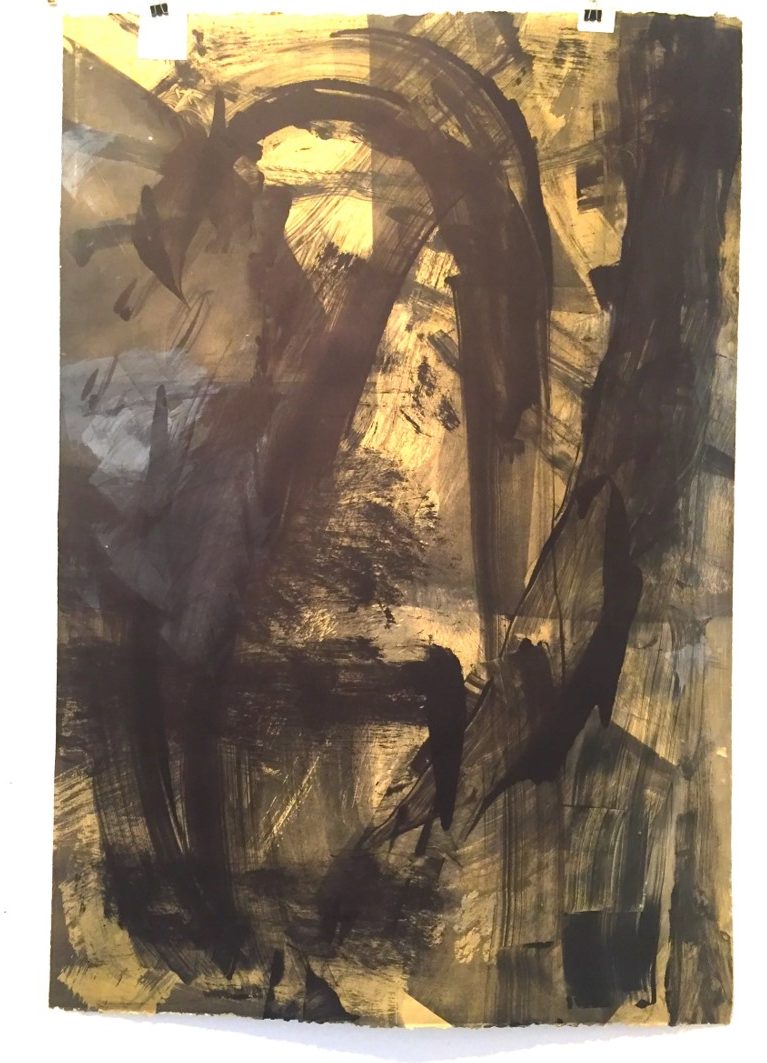

I’ve also done a series of self-portraits in oil, one series began the day after the 2016 election and finished on my 70th birthday. Most recently, I completed a group of monoprints that examine repetition translucency and presence.

Overall, has it been relatively smooth? If not, what were some of the struggles along the way?

I had thought that the quality of my work would exempt me from the prejudice and constriction suffered by earlier generations of women artists. It did not. In 1982 I gathered statistics comparing teaching positions, reviews, and exhibitions of women and men in Boston. They were unequal. Naming the situation made it easier for me to work. I thought about that until it seemed funny. In 1989 I drew a satire “The Book of Penis!” published in 2010 by Pressed Wafer Press.

Though this graphic novel has sold out on Amazon, it is still available from Small Press Distribution. Being an abstract artist in Boston was difficult in 1972 when The Boston Museum of Fine Arts had no contemporary department. I joined the Boston Visual Artists Union, where I met other artists. We lobbied for the inclusion of contemporary art and greater consideration for area artists. Things improved. Carl Belz showed local artists at the Rose Museum, Cliff Ackley at the MFA looked at and purchased art made in Boston, The Ica began annual exhibitions focused on Boston artists.

The deCordova concentrated on contemporary New England art. The Massachusetts Cultural Council began supporting Massachusetts artists with grants. The Maud Morgan Prize continues in its support of local artists as does the Mass Cultural Council.

Regrettably, none of the other programs continue. Further, the habit of collecting work for personal reasons is in decline. Often collectors look for famous names, rather than for unique experiences… This makes collections homogeneous and compounds the difficulty for those of us who are not household names…

Please tell us about more about your work.

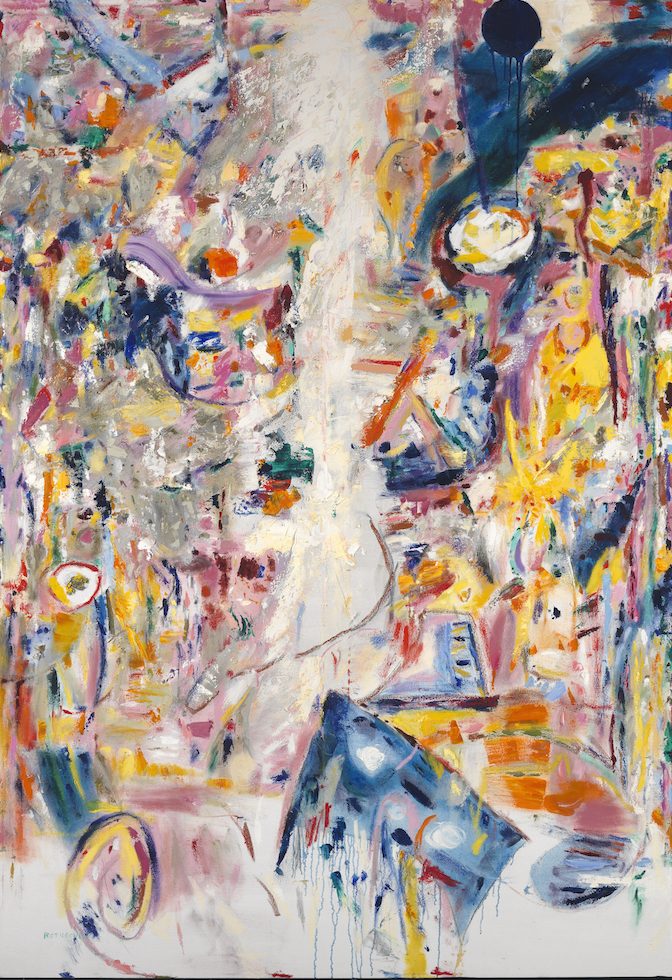

I make oil paintings, like “Fall Walk” the abstract oil currently at “Matter and Light Fine Art” in Boston. I also work on paper. I recently produced a series of large-scale monotypes. A few years ago, I started life drawing for the first time in 30 years.

Some of the figures appear in recent paintings. My method is always exploratory. I don’t know how something will look before it’s finished. I learn as much as I can on the way.

That’s what keeps the process interesting for me, and hopefully makes work rewarding for the viewer. Looking is a matter of discovery.

If you had to go back in time and start over, would you have done anything differently?

Below is an essay I wrote for the Mass Cultural Council. They asked what advice we would give our younger selves:

When I had just moved to Boston and had just gotten my BA, I went to the Boston Visual Artists’ Union for companionship and information. I complained to an older, more confident artist, not about the situation for artists, which has never been easy, but about the clumsiness of my own character and how poorly it matched other, more accomplished people. She (her first name was Virginia, but I’ve forgotten her last name.) said, “Plant a radish, get a radish,” quoting The Fantasticks. I was stuck with myself.

As a young painter, and even as an older painter, there are times when I wish for capacities that other people have: ease in self-promotion, a greater understanding of three-dimensional space, better casual conversation. But at 71, I’m pretty certain that major character changes are both unlikely and undesirable. Sometimes people pay attention to what you are doing, there are places to show, there are reviews and sales.

Sometimes none of that is true. It is difficult to find words for thoughts about painting. Friends who struggle with you to understand what you are doing increase your understanding of yourself and your work.

My younger self-painted no matter what was going on outside. But there were periods of great loneliness and uncertainty. I would remind my younger self that the best paintings come from who you are, rather than in spite of you. Good work comes from allowing the incomplete painting to speak to the imperfect painter and allowing that flawed artist to respond to the painting. It is a constant conversation. This doesn’t guarantee good work, but these are the minimal conditions for grace.

Pricing:

- The Book of Penis! care of Small Press Distribution: https://www.spdbooks.org/Products/Default.aspx?bookid=9780982410035 $17.50

- Paintings: range in size from 8″x8″ to 84″x96″ in price from $900-$24,000

- Drawings: $250-$1450

Contact Info:

- Address: 535 Albany Street 4th Floor

Boston, MA 02118 - Website: joannrothschild.com

- Email: jaroths@comcast.net

- Instagram: Jo Ann Rothschild

- Facebook: Jo Ann Rothschild

Image Credit:

Stacy Friedman, Clements Howcroft Photography, Stewart Clements

http://www.matterlightfineart.

Getting in touch: BostonVoyager is built on recommendations from the community; it’s how we uncover hidden gems, so if you know someone who deserves recognition please let us know here.